Chapter 5: Narrowcast Media

The media shapes our lives in a bigger way than we can ever imagine. In our adult lives, the act of

consuming new information about the world is the constructive function of our actions, behaviors, and

beliefs.

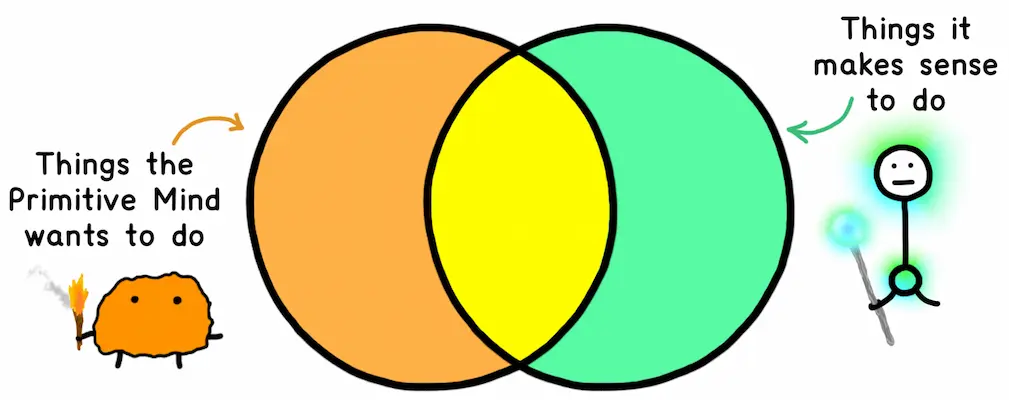

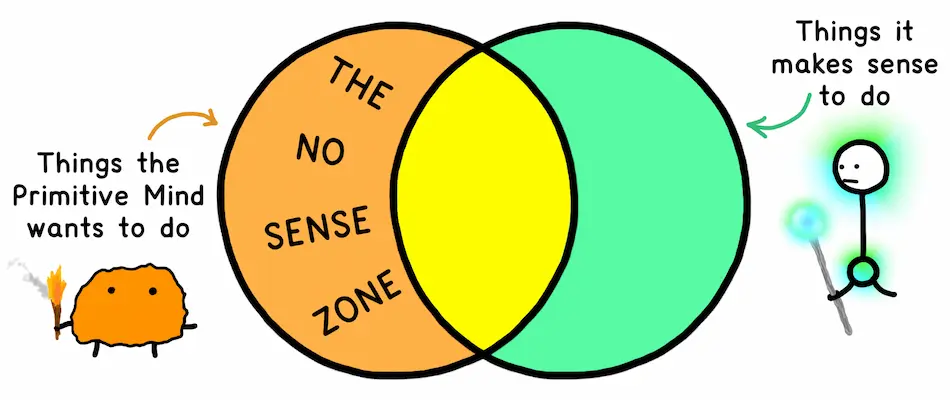

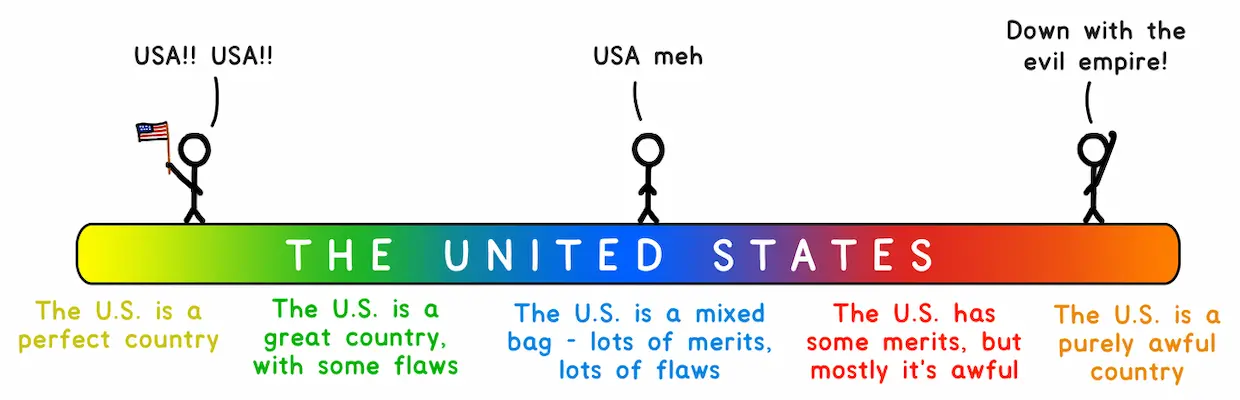

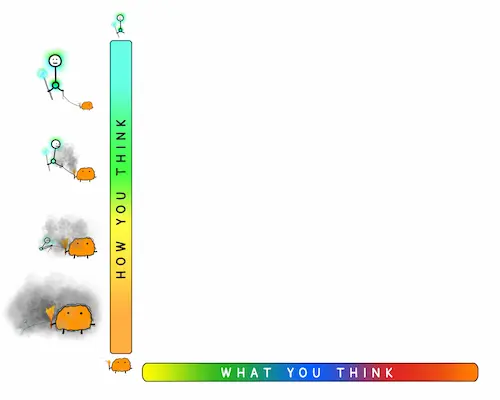

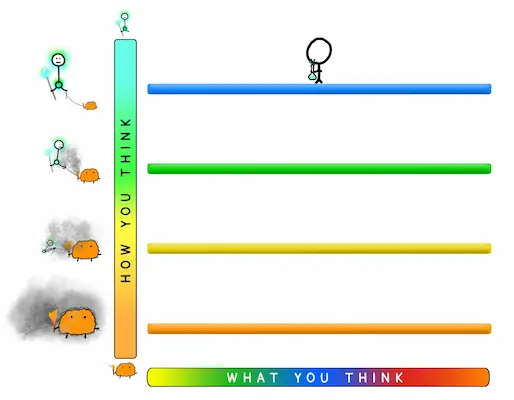

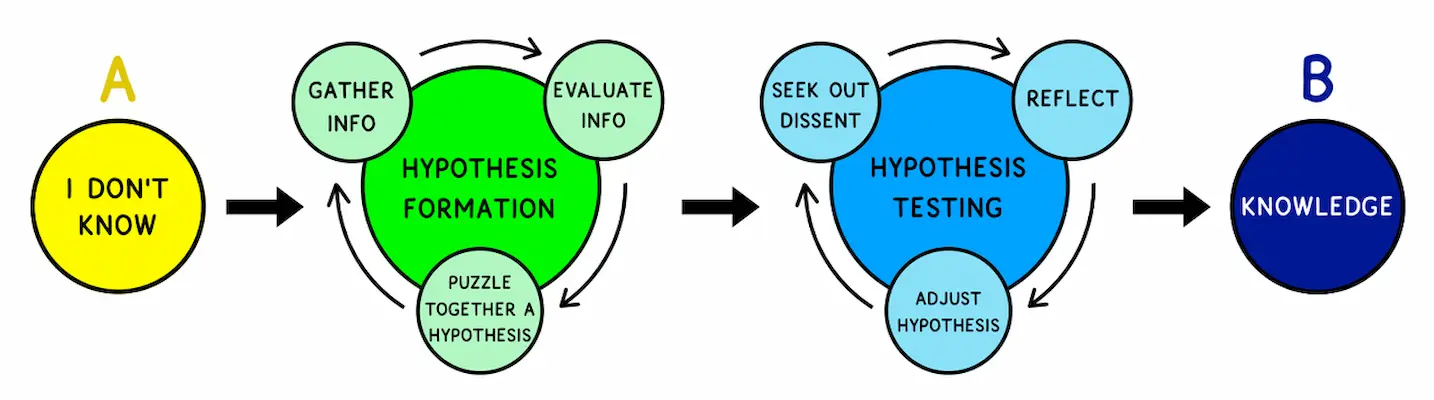

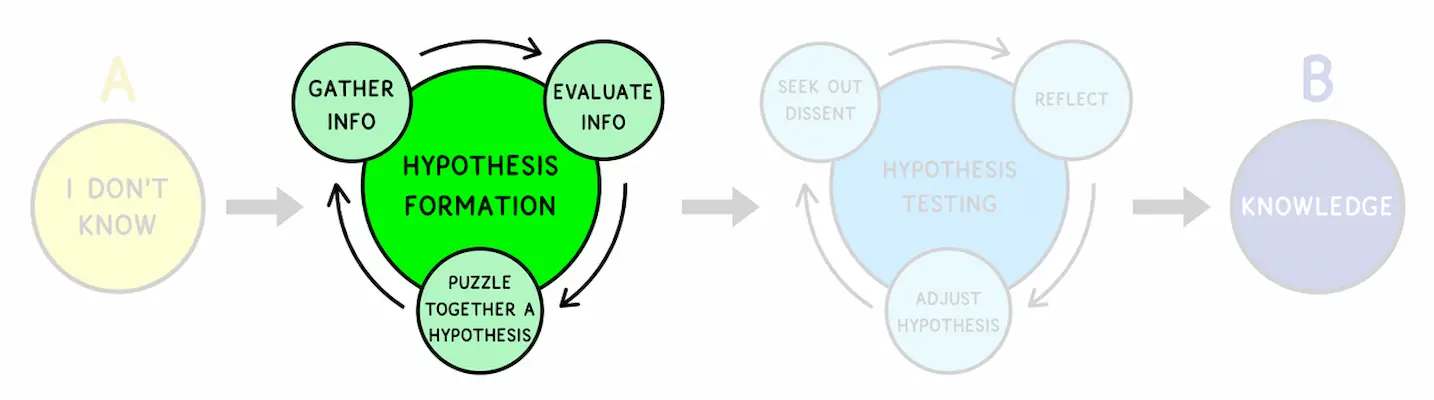

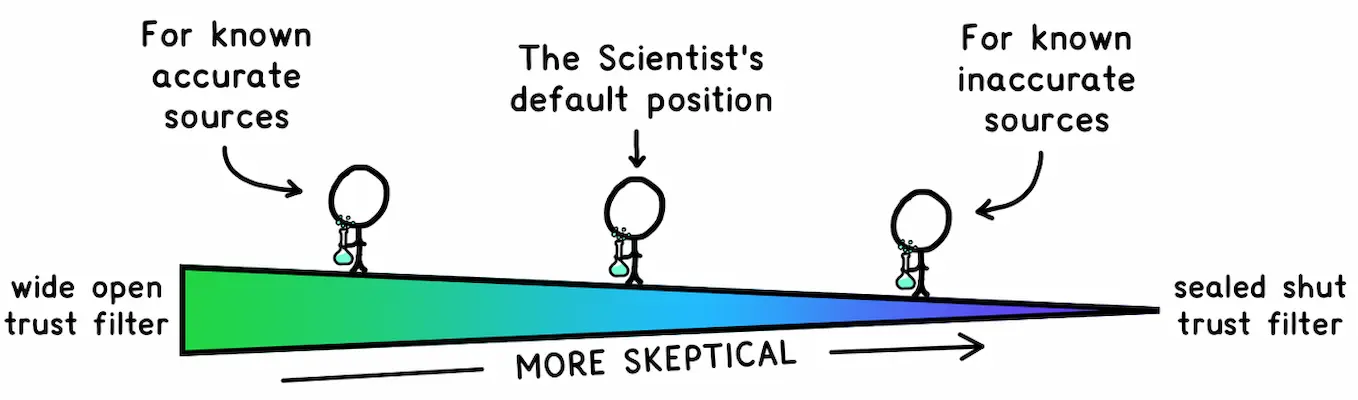

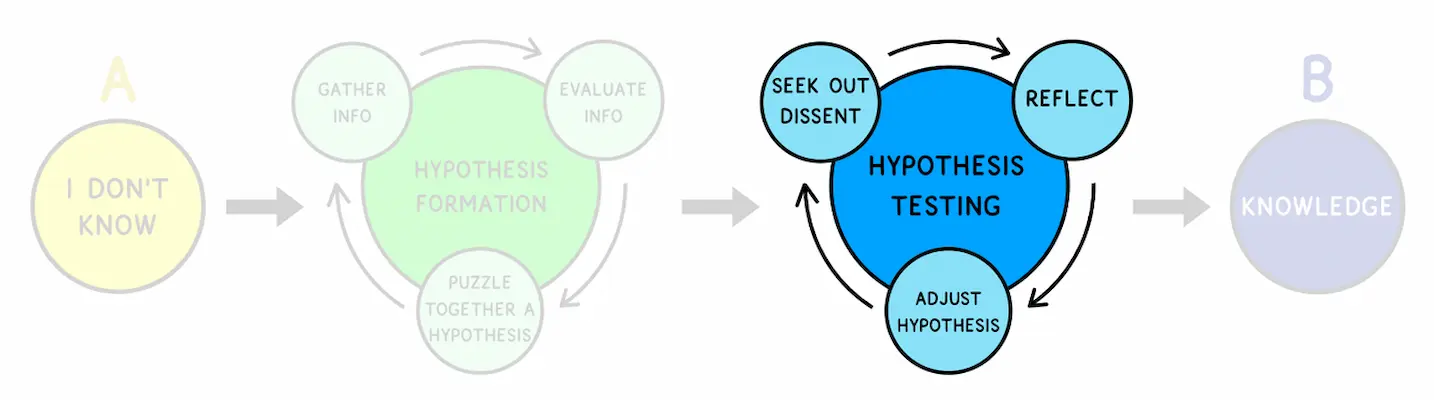

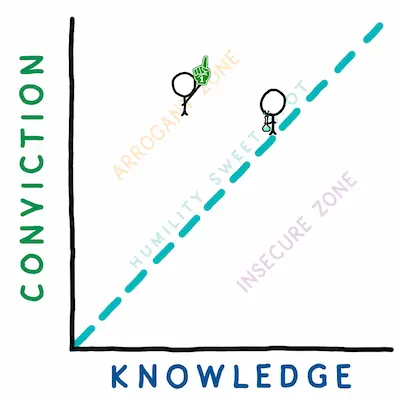

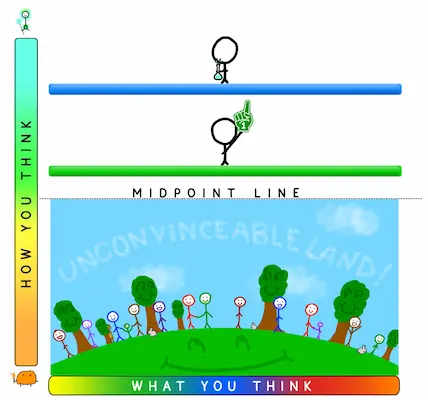

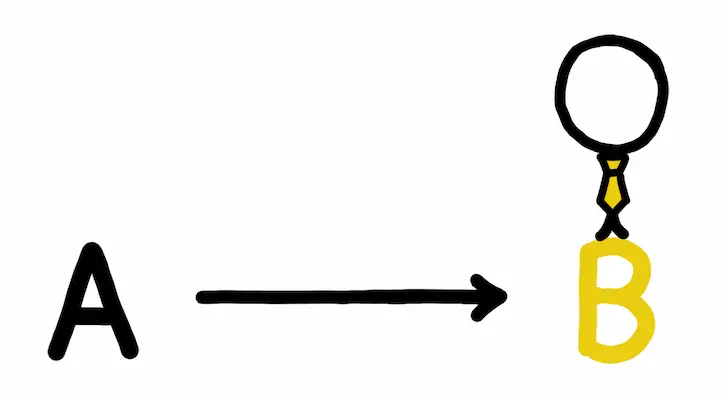

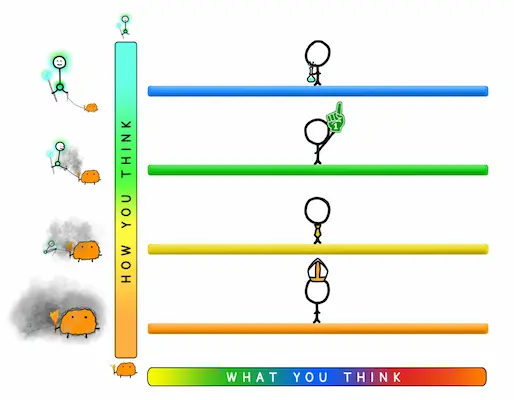

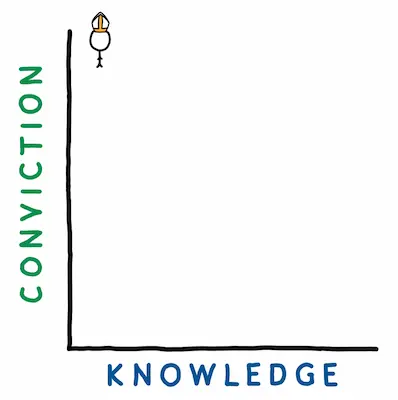

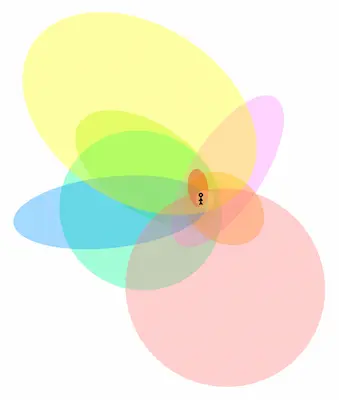

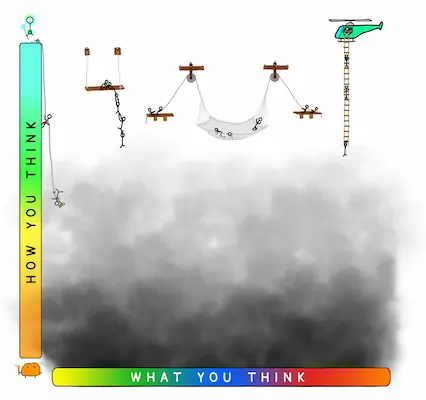

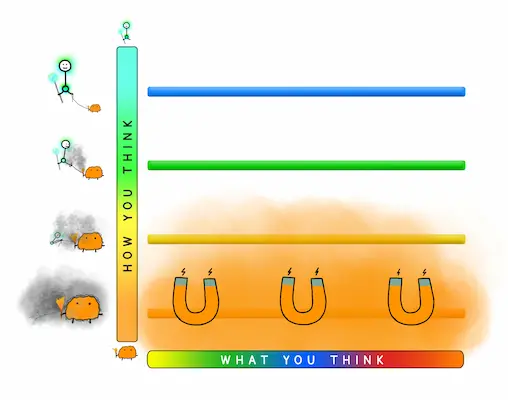

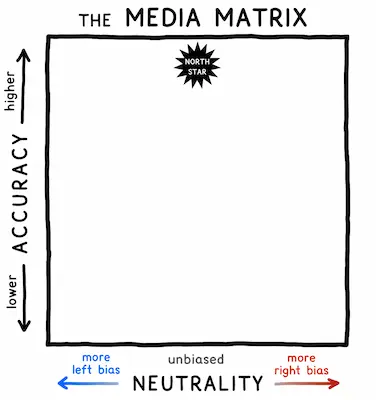

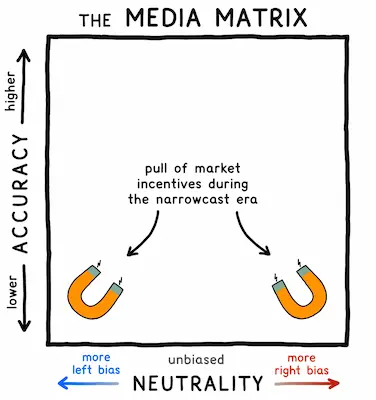

If we look at all our consumption of media, our goal would be to have the most accurate, unbiased, and

personally empowering media possible. This is an ideal however, below is a chart displaying one spectrum of

a media plot, with a north star representing the goal.

Every media brand, media personality, or journalist can be plotted somewhere in the matrix.

At the top-middle of the Media Matrix is media’s North Star. Here you have media sources that are rigorous

about both accuracy and neutrality, trying their best to present the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but

the truth—along with acknowledging when they don’t know what the truth is. This is the realm of high-rung

journalism.

As you move to the left and right of the North Star, political bias begins to creep in. Media voices will

tell most of the story, but they may omit certain unhelpful-to-their-cause stories. When you get all the way

to the upper corners, you have brands with a serious bias—careful about accuracy but not about neutrality.

Everything they report is carefully cherry-picked.

As you move down in the Media Matrix, accuracy diminishes as a core value in favor of profit,

entertainment, a political agenda, or something else. A news source down here is a steadfast ally to its

partisan audience, and it stays current with the latest talking points in Political Disney World, even if

that means twisting stories, using misleading statistics, pulling quotes out of context, treating rumors as

facts, or any other form of bullshit.

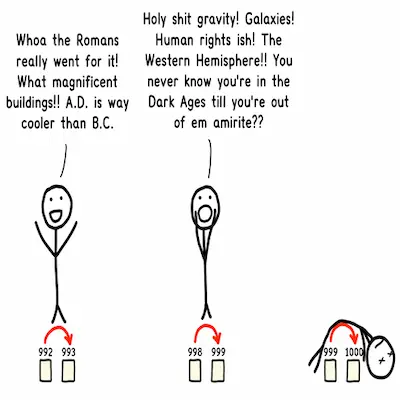

From broadcasting to narrowcasting

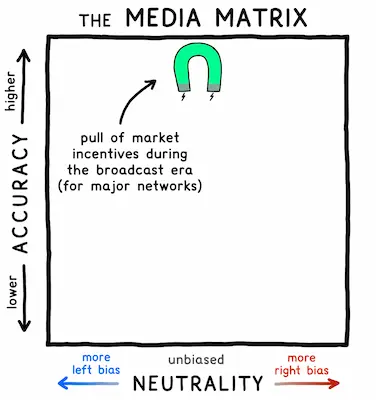

In the 1980s, most Americans got their TV news from the Rather/Jennings/Brokaw trio on CBS, ABC, and NBC;

in earlier years, from nationwide titans like Walter Cronkite. In those days, networks competed to capture

the largest share of American viewers. They were careful to avoid seeming politically biased and they knew

that reporting a story incorrectly could lead to damaged credibility and a loss of viewers. They were

incentivized by market forces and

government regulation not to stray too far from the North Star.

In recent decades, new technology has dramatically changed this landscape.

First, there was the explosion of cable television around 1980, and

with it, the advent of 24-hour cable news (CNN launched in 1980).

Cable channels, with hazier expectations than mainstream networks

and 24 hours a day to work with, could be more experimental with the

way they covered the news.

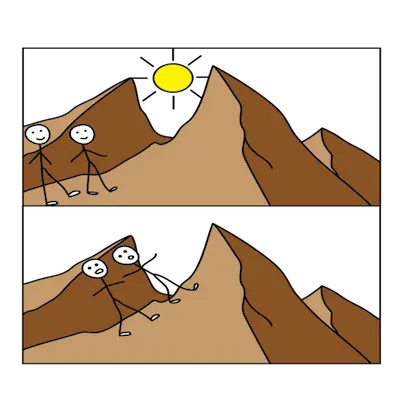

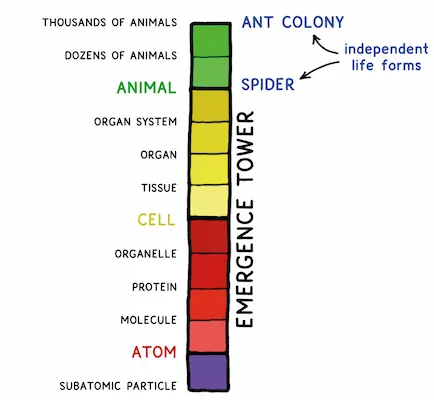

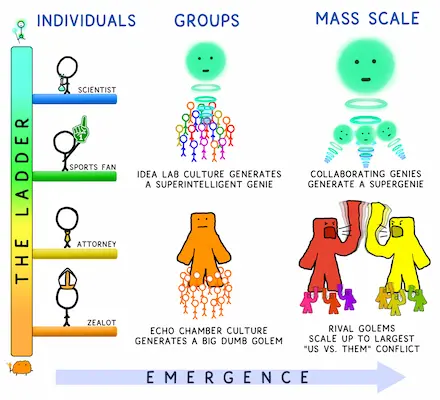

Take ants and spiders. Ants are furiously loyal. They always put

the team first. The ants I’ve gotten to know in my life have a

long list of bad personal qualities, but “individual selfishness”

isn’t one of them.

Then there was the end of the Fairness Doctrine. In 1949, the FCC

(the U.S. Federal Communications Commission) established the

Fairness Doctrine, which required anyone who held a broadcast

license to present “controversial issues of public importance” in a “fair

and balanced” manner, giving airtime to “contrasting viewpoints.” In

1987, in the face of arguments that the Fairness Doctrine was in direct

conflict with the First Amendment’s freedom of the press clause, it was repealed.

The removal of the Fairness Doctrine was soon followed by a sharp

rise in overtly partisan media. Conservative talk radio exploded onto

the scene in the late 1980s, most notably with The Rush Limbaugh

Show, which debuted to a national audience in 1988 and made

Limbaugh the country’s most syndicated radio host by 1991. In

1996, Fox News and MSNBC were born. Rather than broadcasting to

all of America, these new media channels could narrowcast to a

specific subset of the country.

In college in 2004, I attended a live interview with Ted Koppel, the

anchor of ABC’s late-night news show Nightline. I remember the host

commenting that Koppel was famously secretive about his own

political leanings. This was the standard for prominent anchors in the

past, but by the end of the 1990s, a huge portion of Americans were

getting their news from people whose political leaning was supremely

out on the table.

While these changes were happening, the internet sprung into our

lives, and with it, sites like The Drudge Report (1995), Slate (1996),

The Huffington Post (2005), and Breitbart (2007), along with a trillion

political blogs and YouTube channels. The internet took narrowcasting

up into a new gear: full-fledged tribal media.

Meanwhile, Fox News and conservative radio continued to grow in

size and influence, generating an insular right-wing information

bubble that persists today. This was countered with a new genre of

TV news on the Left—political comedy shows. The Daily Show began in

1996 and became a multi-decade sensation by serving as—depending

on who you ask—either the voice of reason and sanity in the face of

growing right-wing madness, or a show where elitist progressives

would cackle as Jon Stewart relentlessly mocked their political out-

group. The Daily Show was followed by a slew of similar “look at how

awful the Right is” comedy/news shows, hosted by Daily Show alums

like Stephen Colbert, John Oliver, and Samantha Bee.

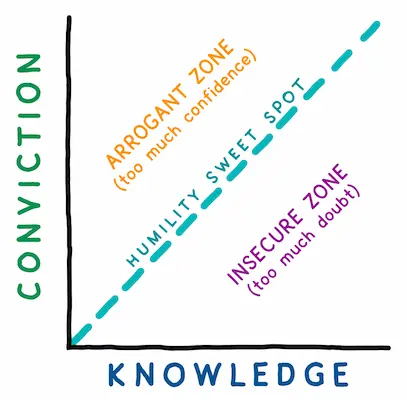

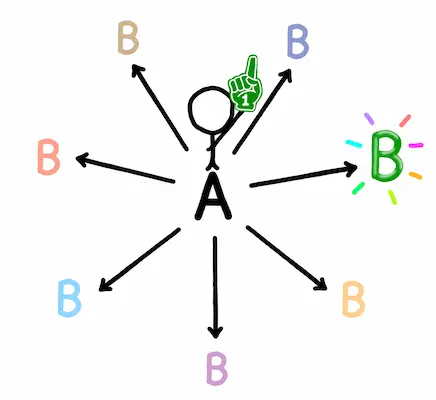

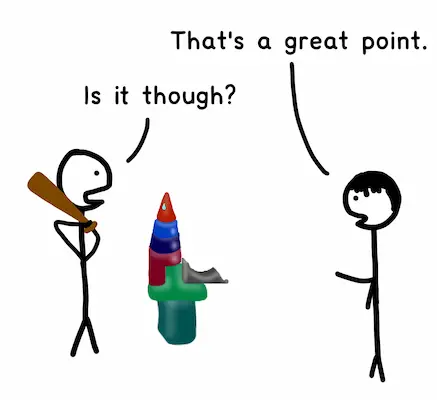

Narrowcast media caters to homogeneous audiences, which

decreases the incentive to worry about neutrality and heightens the

incentive to provide viewpoint confirmation. Rather than tell people

which candidate is likely to win the next election like the old days,

narrowcast media reaps huge rewards for telling people why their

favorite candidate ought to win. With little risk of reputation

damage for biased coverage, narrowcast media can continually bash

one side while giving the other side a free pass and end up with a more

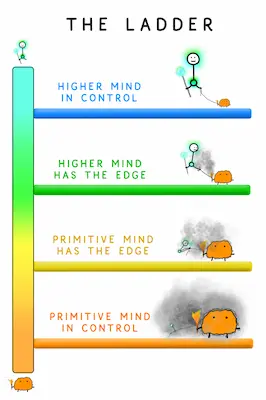

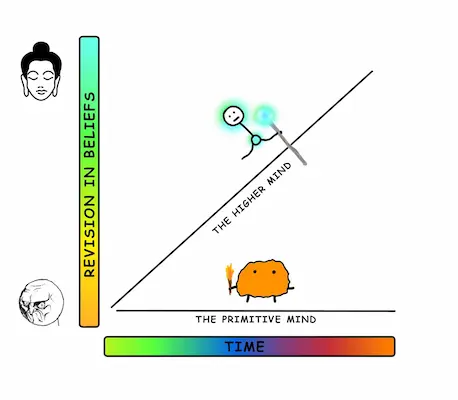

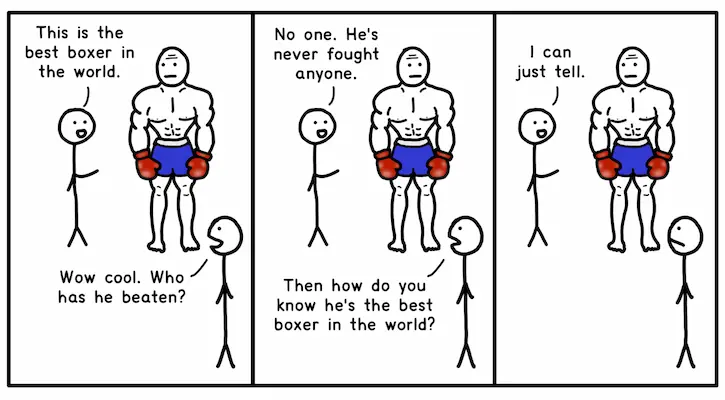

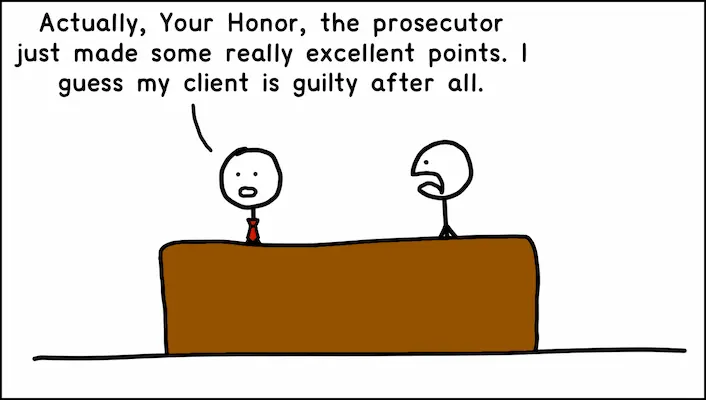

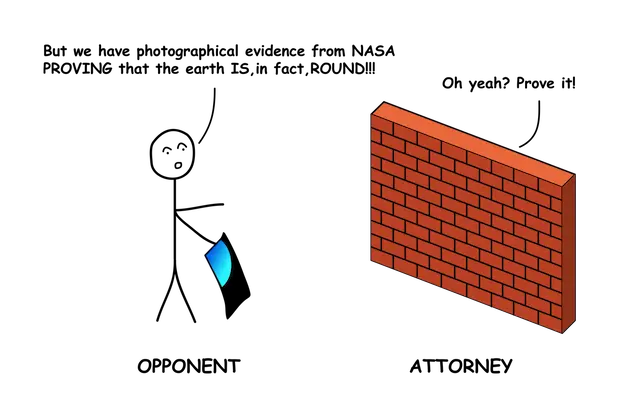

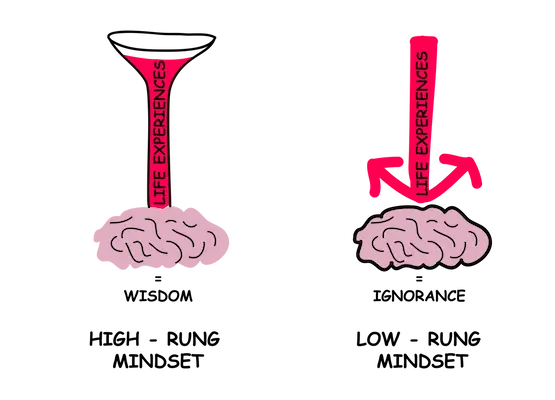

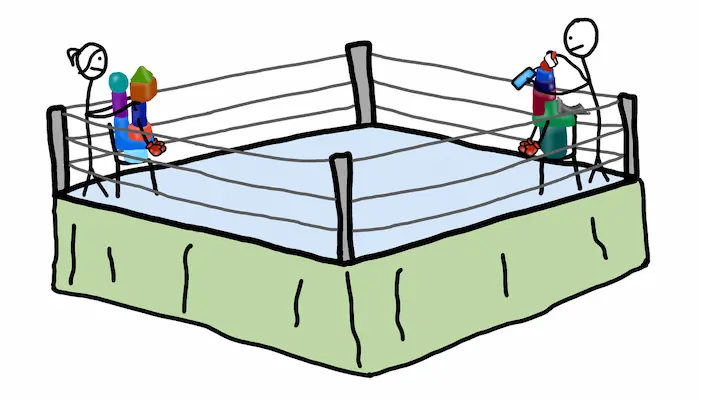

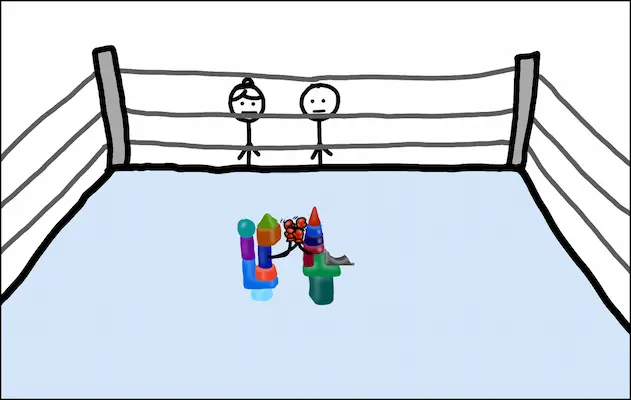

loyal audience for it. If broadcast media functions like a top-rung

Scientist, narrowcast media functions like a third-rung Attorney.

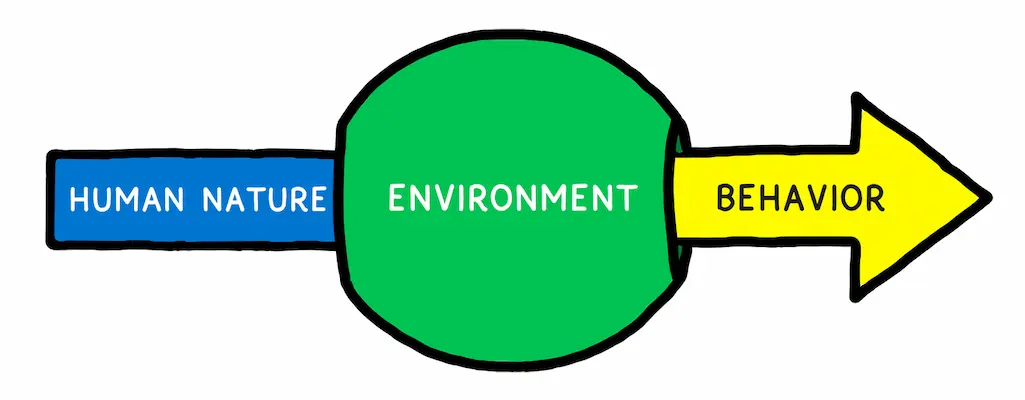

Because when the environment changes, so does behavior.

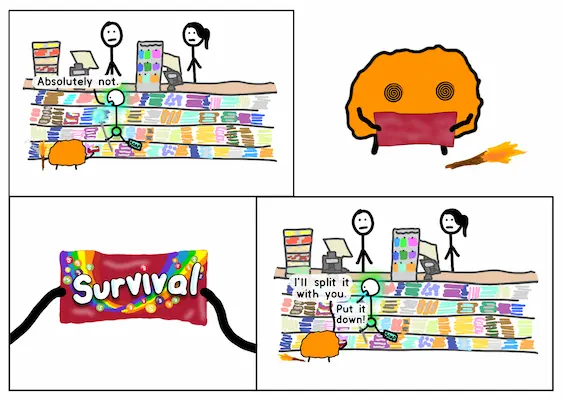

Junk food

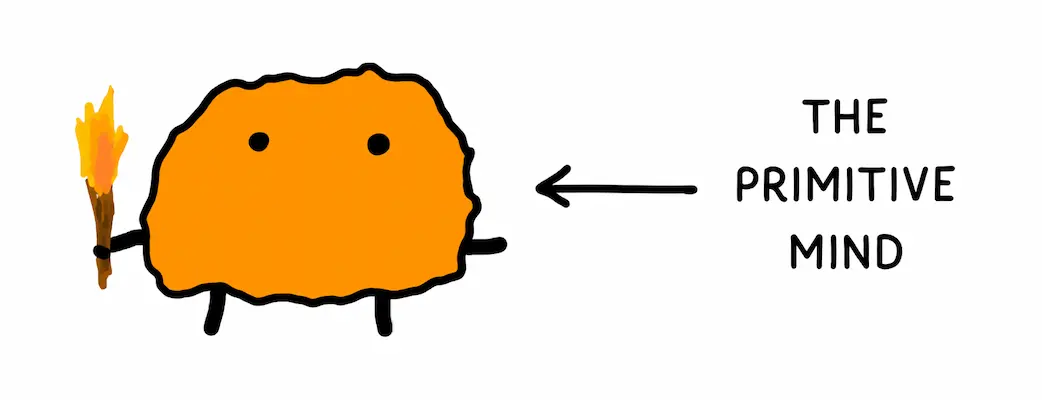

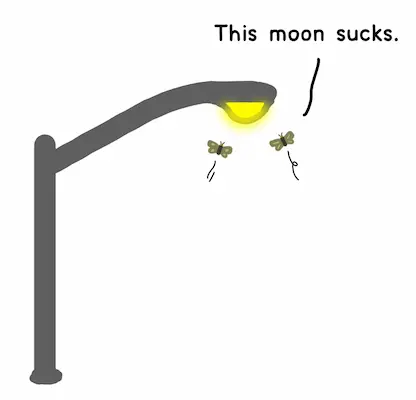

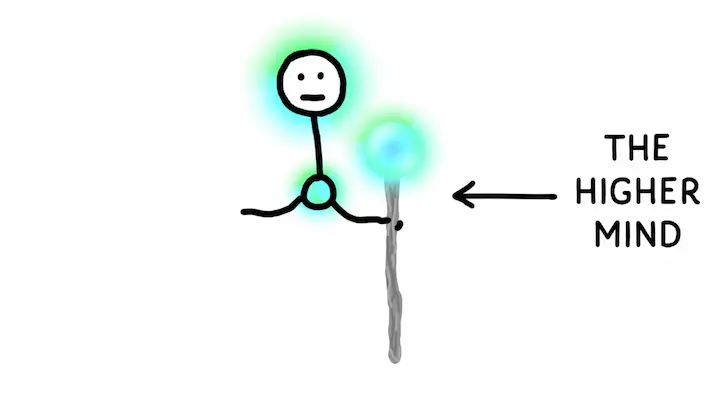

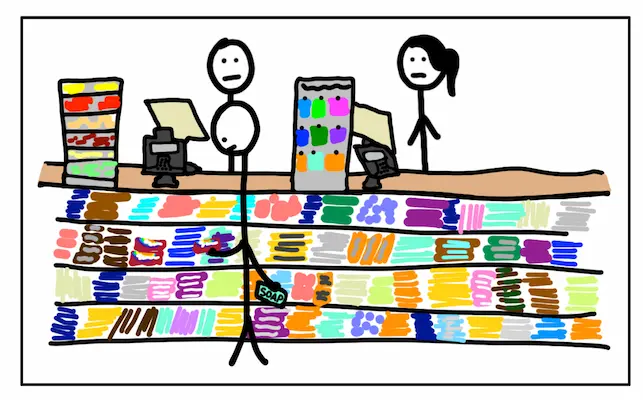

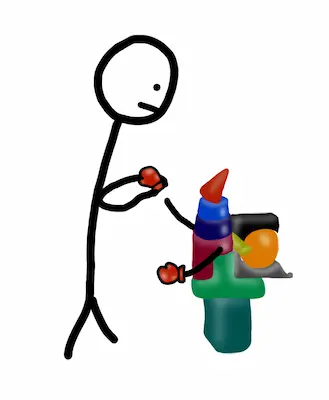

Many businesses have learned that a great way to make money is to

sell directly to the simple, predictable Primitive Mind. To sell food to

the Higher Mind, you have to worry about quality and nutrition, which

is expensive and hard. Instead, you can sell Skittles to the Primitive

Mind, who mistakes them for nutritious food.

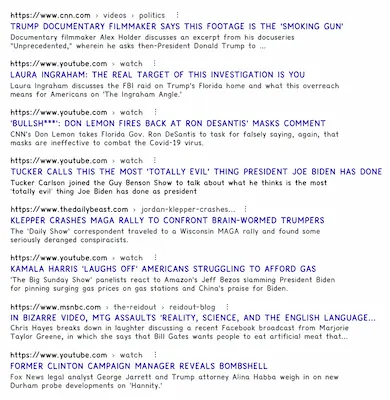

If professional news coverage is nutritious food, political junk food

looks like this(all actual headlines):

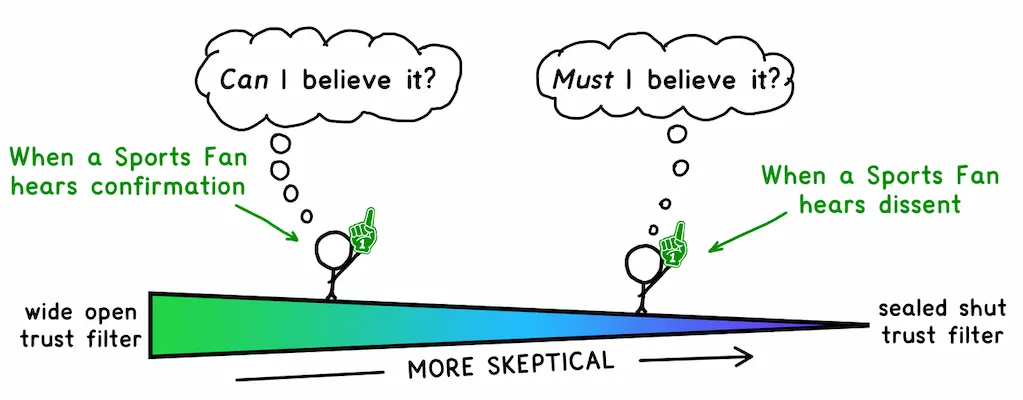

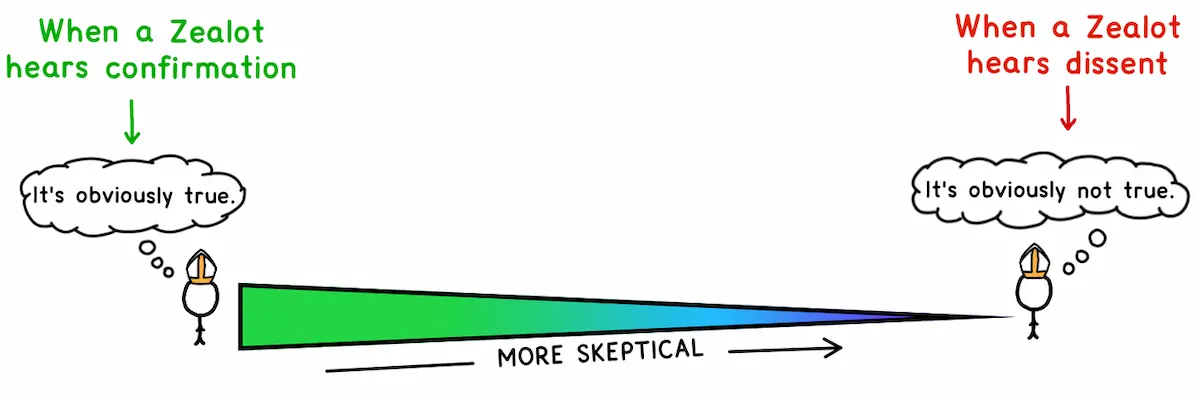

The confirmation promised by these kinds of headlines looks as

delectable to the Primitive Mind as the sweet sustenance promised by

a Skittles wrapper. Political junk food isn’t geared toward learning. The

headlines tell you from the get-go which side will win and which side

will lose. It combines three of the Primitive Mind’s favorite things:

viewpoint/identity confirmation, out-group bashing, and gossip.

The explosion of the political junk food market has dragged many

American minds downward into Political Disney World, the land of

good guys, bad guys, and simple storylines—which in turn has

continually raised the demand for junk food.

The further this cycle goes, the harder it is to reverse. Media brands

that offer up one-sided tribal junk food end up alienating high-rung

minds, which makes the brands that much more dependent on the

junk-food-loving low-rung audience. And tens of millions of Americans

end up with political diabetes.

As the media junk food industry has grown and matured, it has

increasingly immersed its audience in a new, hideous genre of

entertainment:

Political reality TV

Broadcast TV news aimed to be a show about reality. Narrowcast

news tries to be a reality show. Big difference.

Reality is interesting sometimes. Reality shows are interesting all

the time. And what’s the reality TV producer’s best trick? Drama and

negativity. Would anyone watch The Real Housewives of Beverly

Hills if the characters got along most of the time? Of course not. That’s

why every five minutes of the show includes a conflict of some kind.

As soon as you realize that news media is also entertainment media, the constant coverage of conflict and

drama makes perfect sense. In the U.S., many of us are addicted to a trashy reality show I call The Real

Politicians of Washington D.C.

The cast changes from year to year, but the formula is the same:

there are whole teams of heroes and villains, lots of ongoing

storylines, and endless conflict. It’s a perfect vehicle for a dramatic,

super-addictive soap opera.

It’s not that these heavily featured politicians or the played-up

storylines are unimportant. It’s that we receive a

totally skewed depiction of the full set of relevant political issues. The

issues that make headlines day in and day out are usually

overrepresented, while lots of other important political stories—like

the bills being approved each week by the 50 House and Senate

committees—are woefully underreported.

I recently had a chance to talk with a U.S. representative

named Derek Kilmer. Kilmer is the former head of a major

congressional coalition of moderate Democrats with 99 members.

He’s full of nuanced, measured, well-thought-out ideas for how to

make the country better. Which is exactly why you’ve never heard of

him. The editors of The Real Politicians waste no airtime on politicians

like Kilmer because he’s measured and nuanced and I’m falling asleep

just writing this sentence.

Actual politics, like actual reality, is boring to most people. So tribal

media brands do what reality TV producers do—they manufacture a

carefully edited, fictional version of politics that’s wildly entertaining.

That’s why most Americans who will tell you they’re passionate

about politics can barely name ten current members of Congress. They

probably can’t name all the U.S. representatives from their state, let

alone members of their state legislatures. But they can tell you about

the 10 or 15 politicians chosen by the media to be the main characters

on The Real Politicians, along with the five or ten hot button issues the

show features in any given month.

Concentrated tribalism has led to increased division—but The Real

Politicians adds fuel to the fire by making the distinction between the

parties seem even more stark than it actually is.

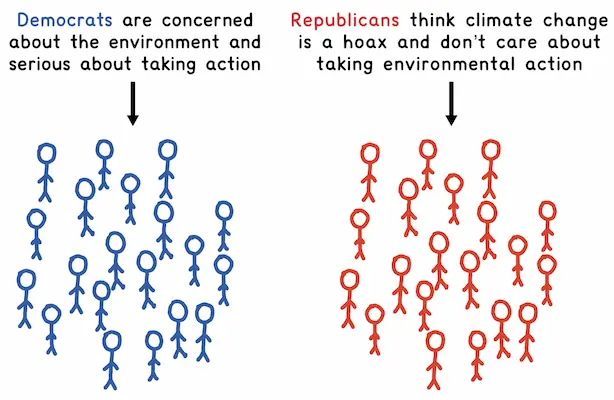

Take the issue of climate change, where we’re regularly presented

with this storyline:

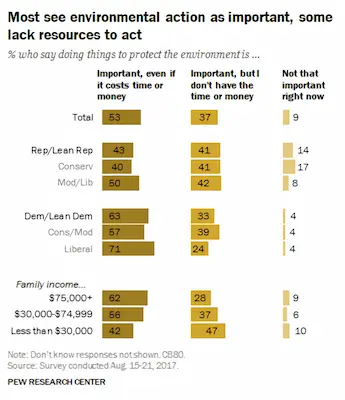

So I was surprised to see this data:

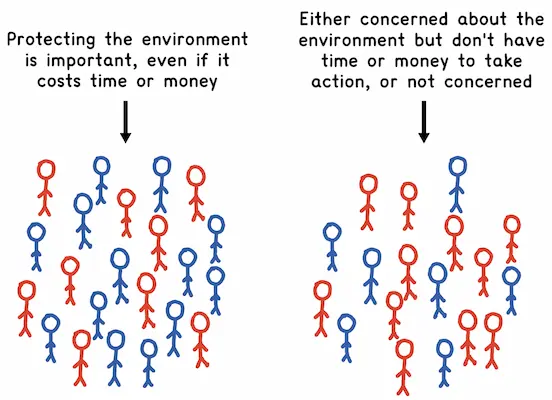

Which suggests that things are more like this:

Very different story. Of course, it’s also true that many Republican

politicians have been dismissive of climate change. And “doing things

to protect the environment” is not necessarily the same as taking

action to curb emissions. But the survey makes me feel very differently

about the strategies climate activists should be using to build the

necessary coalition to change our trajectory.

Presenting an inaccurate version of reality breeds misplaced anger

and division and hurts our ability to move toward important goals—all

in the name of editing the reality show to be more entertaining with

crisper, juicier storylines.

The most dramatic events on The Real Politicians are elections.

Elections are the show’s climactic season finales. And the show’s

editors make sure to over-dramatize the shit out of them.

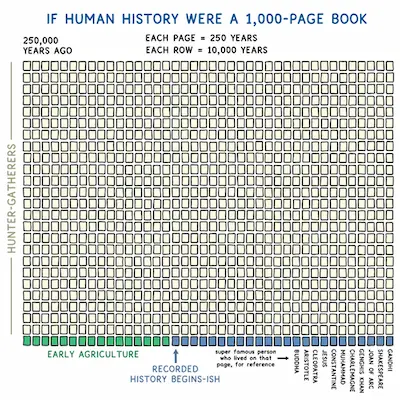

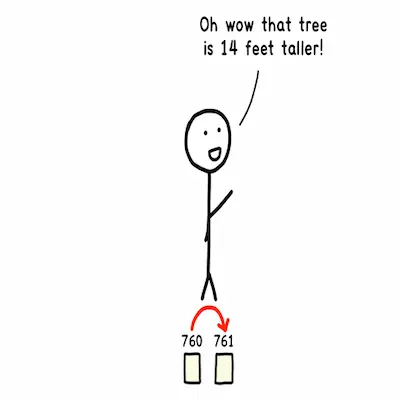

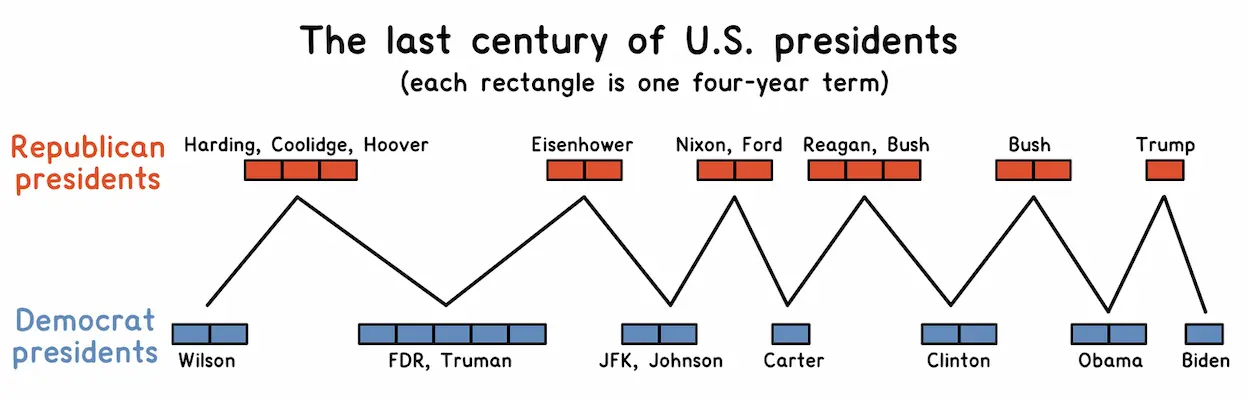

This is the past century of U.S. presidential elections.

It’s a clear zig-zag pattern. And yet, I remember when Bush won

reelection in 2004, media commentators were talking about how

Democrats couldn’t win races anymore for a number of seemingly

rock-solid sociological reasons. Then the Democrats swept the

midterms in 2006 and won the presidency in 2008.

I remember in 2012, when Obama won reelection, hearing people

say that the country had fundamentally shifted, that there were more

first-generation Americans than there used to be, that the Tea Party

had rendered the Republican Party irrelevant, and all of this other

proof that times had changed and the Democrats wouldn’t ever lose a

presidential election again.

Then Republicans swept all three branches of government in 2016,

at which point I read all these articles about how the Left is more

culturally powerful, but the Right is simply more politically powerful. I

also heard a bunch of stuff about how gerrymandering ensured that

the Democrats would never win back the House again. In 2018, the

Democrats won the House and then swept the Congress, Senate, and

presidency in 2020.

I don’t know what truly motivates today’s media. Maybe they make

politically motivated propaganda. Maybe they make profit-motivated

entertainment, which happens to double as political propaganda.

Whatever the motivation, the consequence is the same: enhanced

political tribalism.

Around a decade after the transformation to narrowcasting began,

another technological development added even more fuel to the fire.

Internet Algorithms

I appreciate the Google search algorithm. It filters results that are

most relevant to where I live and what I’m typically interested in, and it

can guess remarkably well what I want to search for after I type just a

few letters, saving me the trouble of typing the whole search.

I appreciate the YouTube algorithm, which knows my favorite

channels and makes sure I never miss their latest videos.

I appreciate the Facebook algorithm, which spares me the

knowledge of what Jake from high school 20 years ago made for

dinner last night while making sure to let me know when Jake gets

engaged, so I can go look through his 87 most recent photos to see the

deal with his fiancé.

Internet algorithms can be great things.

But new technology often comes along with unanticipated

consequences.

When I’m watching a YouTube video and I glance at the thumbnails

on the sidebar, I’m more likely to click on a video featuring someone

explaining history or science than I am to click on a video featuring

someone reviewing movies. YouTube has picked up on that, which is

why I never see movie review videos on my YouTube sidebar, but I’m

constantly being introduced to new history or science explainer

videos.

But then one night last year, someone sent me a funny video a

driver took with their phone. The driver taking the video had pissed off

another driver, who opened his window and started screaming curses.

The angry driver got so worked up that he swung his arm at the video-

taking driver angrily, and in the process, punched his own side mirror

off. A delight of all delights.

Then the video ended, and YouTube offered me my choice of nine

more videos in the road rage genre. I clicked on one of them and

watched it. Then YouTube offered me nine more. I had a lot of work to

do, so I held down the Command key and clicked on all nine, opening

them in nine new tabs, and watched them all. Two hours later, utterly

disgusted with myself, I pulled the dramatic “punishing Chrome by

holding down Command-Q and closing all eight Chrome windows and

all 127 of their open tabs” move. A nightmare waste of time. But at

least it was over.

Except it wasn’t over. Somewhere out there, the YouTube algorithm

was baiting its Tim Urban fishhook with the best of the best road rage

videos, which have reliably appeared in my YouTube sidebar ever since

that regrettable night, damning me to an entire life wasted watching

hilarious road rage videos.

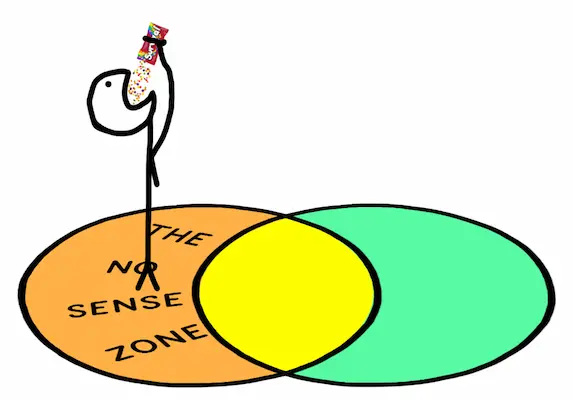

Internet algorithms are profit-maximizing mechanisms that want to

spoon-feed me whatever I’m most likely to click on. This is a win-win,

symbiotic relationship—until it’s not. When an algorithm is jibing with

your Higher Mind, it’s your friend. When it’s luring in your Primitive

Mind against your Higher Mind’s will, the relationship is parasitic.

So how does this apply to politics? Primitive Minds like to click on

political junk food. They’re drawn to articles and videos that don’t just

report the news but sensationalize it and make it entertaining. The

YouTube sidebar can quickly turn into a wall of The Real Politicians of

Washington D.C. content the same way YouTube inundated me with

road rage videos. This feeds political tribalism and distorts our picture

of reality.

Then there’s social media, a phenomenon so peculiar and so specific

to modern times that it would seem incomprehensible to everyone

who came before us. Social media doesn’t just amplify political junk

food, it plays a role in shaping it. When a new political news story

makes waves, thousands of hot takes quickly bubble up. It’s not

necessarily the most accurate takes that rise to the top but those that

are most likely to make people click the retweet or share button—

those that have the catchiest wording and hit the right emotional

buttons. Through an almost evolutionary process, complex topics

are dumbed down and packaged into irresistible nuggets for our

Primitive Minds.

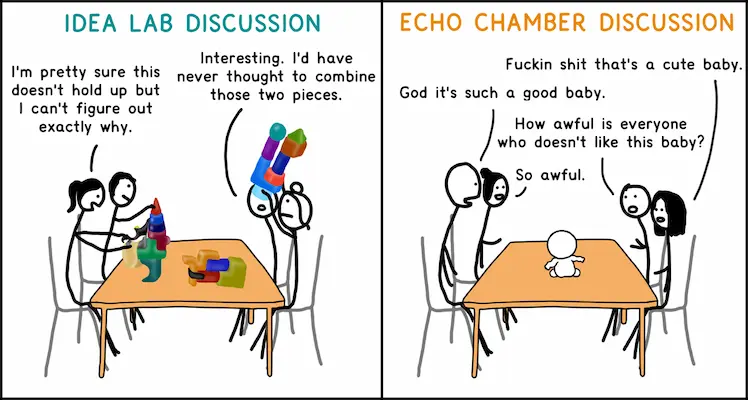

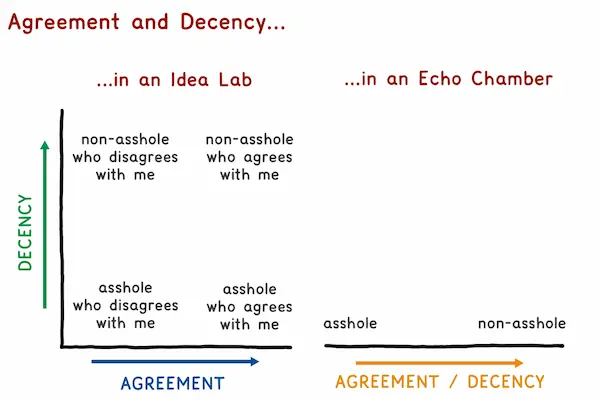

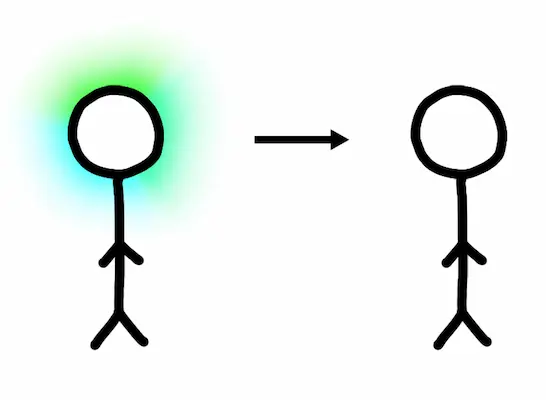

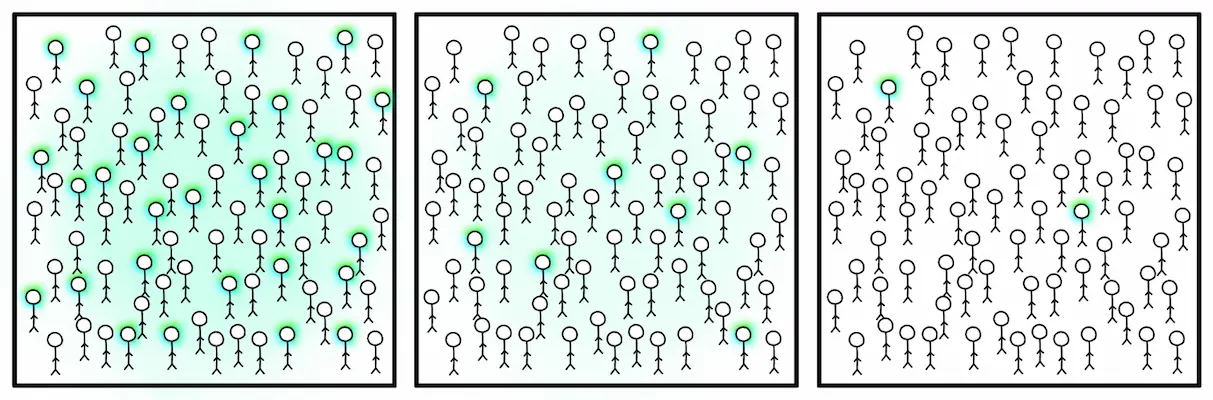

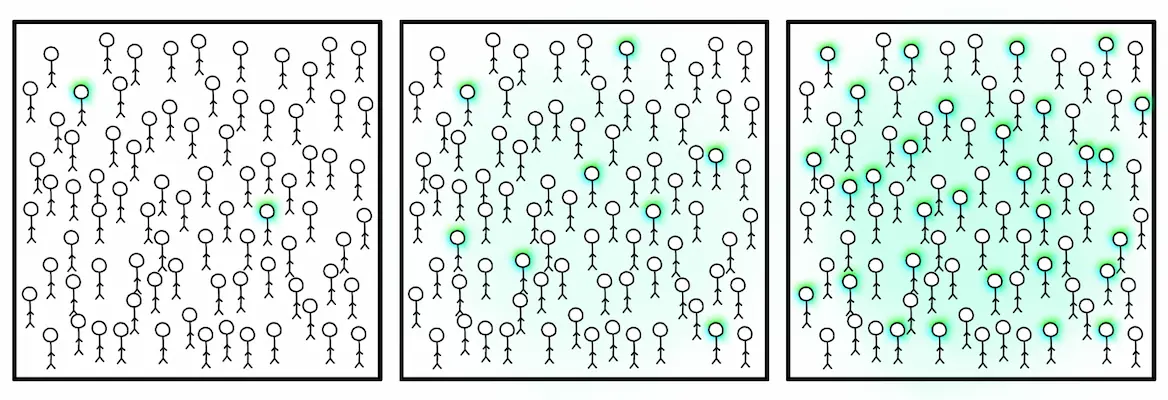

Only a minority of people are hyperpartisan. But internet

algorithms make people who are already extreme even more

extreme. On social media, these voices disproportionately drive the

conversation, making people feel like things are even more nasty and

polarized than they actually are.

In the 2020 documentary The Social Dilemma, computer scientist

Jaron Lanier uses Wikipedia as an example to highlight the craziness

of this situation:

When you go to a [Wikipedia] page, you’re seeing the same

thing as other people. So it’s one of the few things online that

we at least hold in common. Now, just imagine for a second that

Wikipedia said, “We’re gonna give each person a different

customized definition, and we’re gonna be paid by people for

that.” So, Wikipedia would be spying on you. Wikipedia would

calculate, “What’s the thing I can do to get this person to

change a little bit on behalf of some commercial interest?”

Right? And then it would change the entry. Can you imagine

that? Well, you should be able to, ‘cause that’s exactly what’s

happening on Facebook. It’s exactly what’s happening in your

YouTube feed.

What happens on social media often determines what happens in

the actual media. In his book Why We’re Polarized, Ezra Klein talks

about the way journalists choose what to cover—the way they decide

what is newsworthy. “A shortcut to newsworthiness,” he says, “has

always been whether other news organizations are covering a story—

if they are, then it’s newsworthy by definition.”

In the past, audience members had limited ability to influence what

news was covered. But social media changes the equation. “In the

modern era,” Klein writes, “a shortcut to newsworthiness is social

media virality; if people are already talking about a story or a tweet,

that makes it newsworthy almost by definition.”

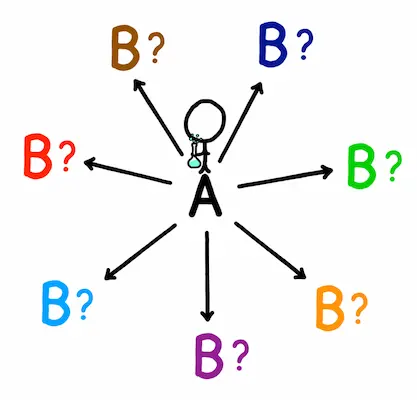

It’s a vicious cycle. As political junk food pulls audiences further into

Political Disney World,23 the low-rung narratives go more viral, more

often, on social media. These viral narratives are then converted into a

wave of new junk food media content, which reinforces and legitimizes

the ideas circulating on social media. The connectivity of the internet

melds media and its audiences into a single self-perpetuating system.

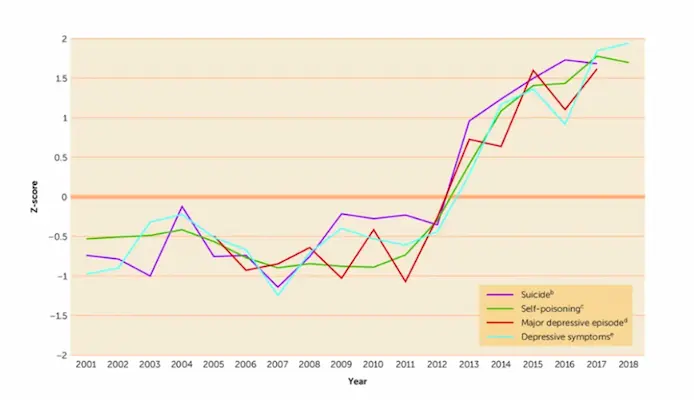

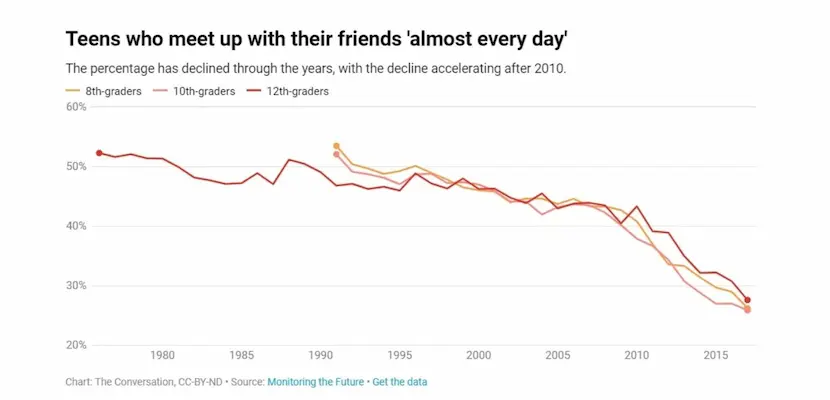

It's no surprise where all this leaves us.

Separate Realities

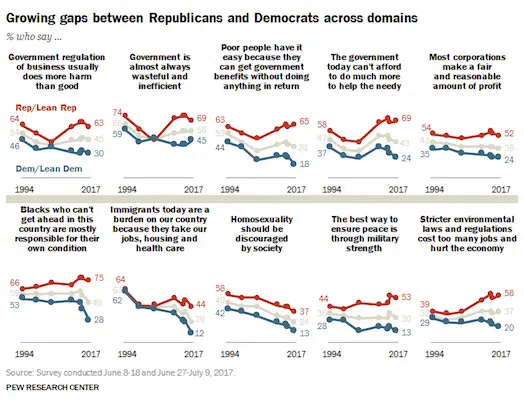

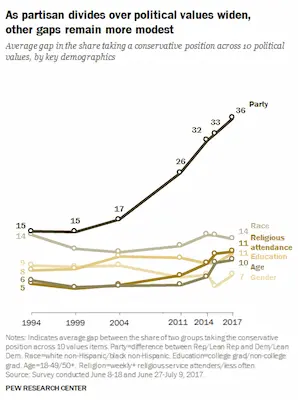

Pew data, collected since 1994, shows us that the gap between the

viewpoints of Democrats and Republicans has grown on a selection of

issues across the board:

Averaging out the growth of the gap in those ten graphs yields a

smooth upward trend—even as gaps in viewpoints between other

kinds of demographics have remained unchanged:

When we hear about growing political division, most of us assume it

means citizens are divided in their values—that people are unable to

agree about What Should Be. But take another look at the ten

questions from Pew. There’s an element of What Should Be embedded

in some of the questions—but mostly, they are questions about What

Is. Many are statements about the status quo that the two political

sides do not agree on.

We see the same story again and again. A 2020 poll called Dueling

Realities found that 81% of Republicans believe “the Democratic Party

has been taken over by socialists,” while 78% of Democrats believe

“the Republican Party has been taken over by racists.” In 2022, Pew

found that 72% of Americans believe that “on the issues that matter to

them, their side in politics has been losing more often than winning”

while only 24% felt that their side was winning more than losing—a

natural result of political media that increasingly focuses on grievance

and negativity.

A 2017 survey titled “The Parties in our Heads” had an even more

revealing finding: the more political news respondents consumed, the

more skewed their perception of members of the other party.

Separate realities are a natural consequence of market incentives

moving from the North Star region closer to the lower corners of the

Media Matrix, where there’s almost no overlap in coverage between

the two sides. It makes sense that those most hooked on political

media would be the most delusional, the same way consumers of

political news in dog-raccoon-ville left the pro-dog and pro-raccoon

crowds with totally different perceptions of reality.

A Rise in Bigotry

News media is infamous for what we could call “destructive cherry-

picking”—a selection bias that sees negative stories as the most

newsworthy, because they draw the most interest. It’s why, for

example, Americans surveyed by Gallup since 1990 consistently think

crime is increasing, even though in almost every one of those years, it

decreased from the year before.

Destructive cherry-picking spreads fear and pessimism, and over

the past 20 years, it’s been steadily on the rise. In political media, this

can have especially dangerous consequences.

Geographic sorting means many people barely spend time with

anyone on the other political side, so the only information they have

on what those people are like comes through distorted media and

social media filters. The right-wing narrative floods right-wing people

with anecdotes that make it seem like everyone on the left positively

despises them and everything they stand for, and vice versa. Outrage

about these messages then spreads like wildfire on social media.

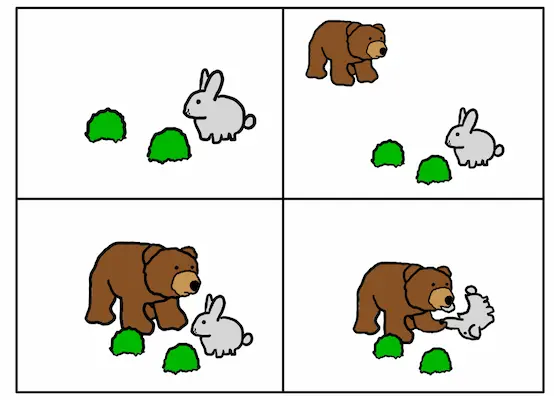

Vocal Primitive Minds activate other Primitive Minds. Presenting

people with a steady stream of “they hate you” jolts awake their

Primitive Minds, in many cases filling them with reciprocal disdain,

clouding their humanity, and flipping on that ancient tribal switch that

makes people want to band together into golems. Portraying a society

where everyone hates each other becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

So it’s no surprise that between 1994 and 2022, the percentage of

people who rate the opposing party as "very unfavorable" has tripled.

It doesn’t take long before this awakens the scariest human

emotion of all: disgust.

Like happiness, sadness, anger, and fear, disgust is a basic emotion,

meaning that it’s hardwired into all humans. Basic emotions were

helpful for survival in the ancient human world. A Google Images

search for “disgust” shows a bunch of people, all making the same

hideous face—squinting their eyes, curling up their noses, and exhaling

(and if it gets really bad, exhaling turns to gagging and eventually

vomiting). Scientists believe this is evolution’s way of getting us to

close up our incoming passages and expel outward whatever we can, in

order to protect ourselves when we’re in the presence of toxins or

disease. We react this way to anything our primitive software believes

is potentially dangerous and disease-carrying—like rotten food, blood,

feces, or maggots.

The strange thing is that disgust can carry over to how we

view people. There’s a sizable amount of research that suggests that

when people are exposed to something that brings out their disgust

emotion, they become harsher moral judges. In one experiment, a

group of Canadians were shown disturbing-but-not-disgusting images

of car accidents while another was shown photos of coughing people

and other disease-related visuals. Then both groups were questioned

about which countries they felt Canada should try to attract

immigrants from. Both groups showed a preference for immigrants

from familiar countries over immigrants from less familiar countries,

but the group that had seen images of disease felt this preference

much more strongly. In another study, participants sitting at a dirty

desk were harsher in their judgments of a series of criminal acts than

participants sitting at a clean desk. In another, a wafting noxious odor

made participants feel less warmly toward gay men.

Scientists use the term “behavioral immune system” to describe the

theory that disgust in humans is linked to xenophobia and discomfort

with practices and rituals (especially sexual) that seem foreign or

different to us—an ancient impulse we developed long ago, when

contact with foreign people and practices often did put you at risk of

disease.

The reason I call disgust the scariest of all human emotions is that

it’s a trigger for dehumanization, and dehumanization is the doorway

to the worst things humans do. It’s not a coincidence that two of the

most horrifying events in recent human history—the Holocaust and

the Rwandan genocide—were made possible by disgust. Nazi

propaganda constantly compared Jews to disgust-inducing animals

like rats, swine, and insects. The Rwandan radio broadcasts that

incited the 1994 genocide referred to Tutsis as “cockroaches”

repeatedly. These are just two examples of a well-worn tradition.30

Disgust fills our mind with a special kind of primitive fog—one that

turns ordinary humans into psychopaths who can commit or condone

unthinkable harm without remorse. Scary shit.

Geographic sorting and political junk food make a lethal combo,

ripe for disgust. It’s hard to feel dehumanizing disgust for people you

know personally. Less hard when you rarely see your enemies in

person. Less hard still when destructive cherry-picking teaches you

only the worst about them. As affective polarization has risen, political

opponents have gone from seeming like wrong or stupid people to

seeming like disgusting people.

We like to think of bigotry as something that other people do. But

we’re all capable of rank bigotry when our environment pushes the

right buttons in our psyche.

Political bigotry is as real as any other bigotry. In a 2014 paper on

political polarization in the U.S., political scientist Shanto Iyengar and

researcher Sean J. Westwood find evidence that “hostile feelings for

the opposing party are ingrained or automatic in voters’ minds” and

that “partisans discriminate against opposing partisans, doing so to a

degree that exceeds discrimination based on race.”⬥

Bigotry is at its most dangerous when it goes unrecognized. The

best tools to combat bigotry are social norms that penalize its

expression—but today in the U.S., political bigotry is rarely treated as

taboo.

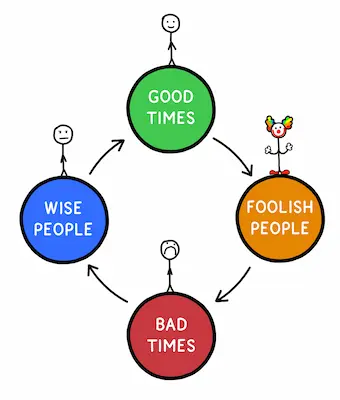

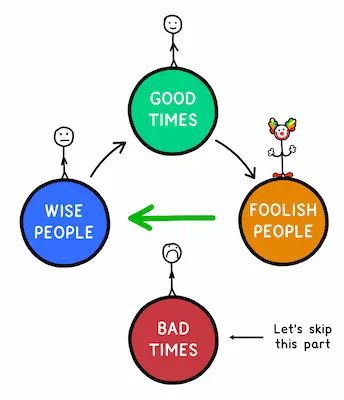

Downward We Spiral

Human environments are made up of a complex fabric of culture,

norms, values, laws, and prevailing beliefs. Changes to any element of

our environment can trigger changes in other parts of the

environment, which in turn can cause more changes.

We discussed the way that the advent of tribal media made people

more partisan and more hooked on political junk food, and how the

resulting rise in demand pushed media to be even more tribal and one-

sided.

A similar feedback loop has taken place between voters and

politicians. Increasingly partisan politicians draw constituents deeper

into Political Disney World, and a lower-rung electorate is more likely

to reward politicians who cater to the low-rung mindset and snub the

politicians who act like grown-ups. As political tribalism has ramped up,

the number of undecided votes has dwindled. It makes less sense than

it used to for candidates to try to persuade moderate voters and more

sense to run hyperpartisan, negative campaigns that fire up their base and

increase turnout.

And as the media’s political coverage has morphed into a reality

TV show, it has created an incentive system that rewards politicians who

use inflammatory rhetoric. As the famously bombastic Representative

Newt Gingrich has put it: “You have to give them confrontations. When you

give them confrontations, you get attention.” Politicians who act like

children are great TV, which incentivizes the media to give them more

airtime, which helps those politicians win elections, which encourages

more of the same behavior.

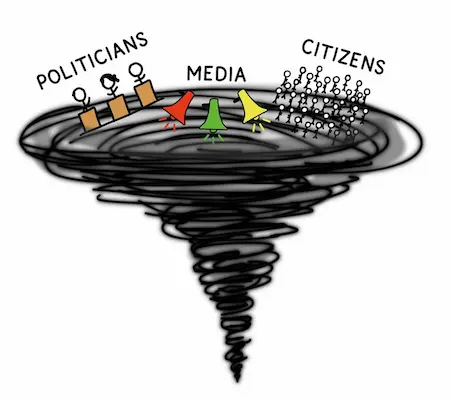

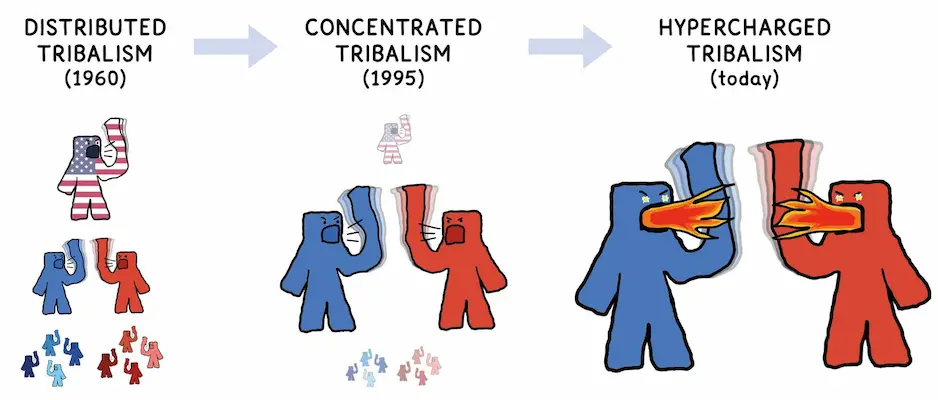

In the first part of this chapter, we talked about how the distributed

political tribalism of the 1960s coalesced into a single, concentrated

tribal divide—an environment that makes a populace more vulnerable

to the pull of the low rungs. When this was coupled with other changes

in geography, media, and social media, it sent the country spinning

down a vortex of negative feedback loops.

This vortex has led us to a scary place I call hypercharged tribalism.

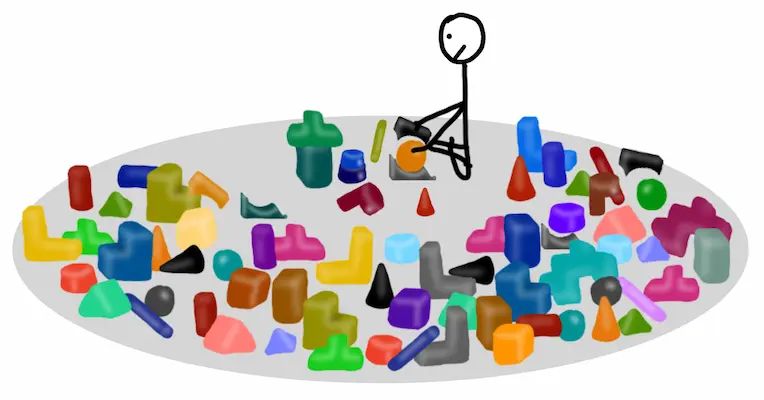

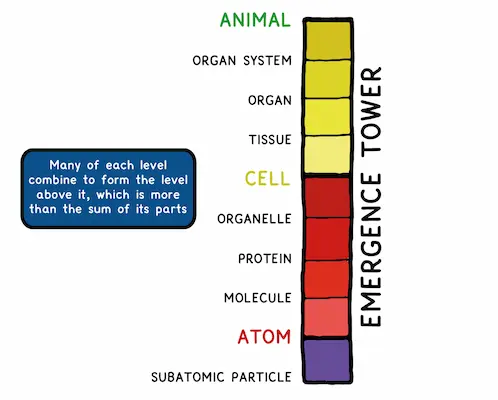

Hypercharged tribalism happens when a concentrated tribal divide reaches such intensity that it resembles a

religious war, subsuming the entire society and the people within it. Hypercharged tribalism turns thinking,

feeling human beings into loyal colony ants, overriding their intellect, their humanity, even their love of

family and friends. It’s a form of group madness—a contagion that spreads like an epidemic, awakening the

ancient survival instincts in millions of minds all at once, as huge groups of people slip into golem mode

in lockstep.